First The Bubble, Then The Burst

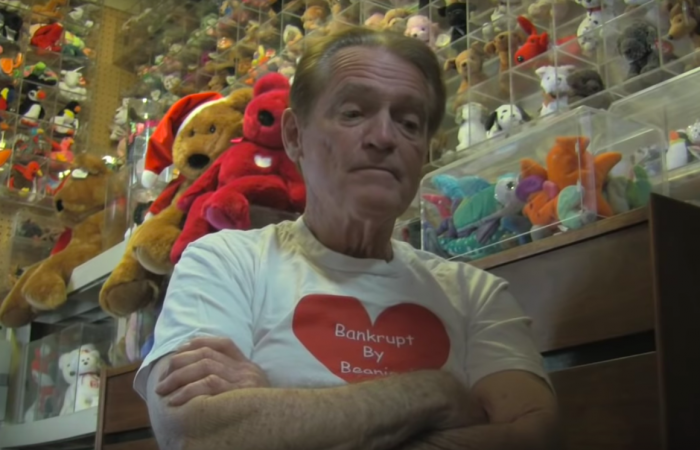

In a suburban Los Angeles garage, Chris Robinson stands uncomfortably, his arms not quite covering the text on his white t-shirt: “BANKRUPT BY BEANIE BABIES.”

“This is like admitting to a drug addiction,” he laments. Behind him, the walls are bricked with boxes and plastic cubes, each packed with $100,000 of colorful plush toys that exhausted the Robinson family’s finances.

“At first it was fun…” Chris says, reminiscing on the weekend hours spent hunting down big-name Beanie Babies in the family Suburban. Robinson often got to know local shop owners, dug up the inside scoop on Beanie Baby release dates and times, and would orchestrate the well-rehearsed household mission, his children in tow: wait in line, pretend not to know one another to circumvent the “one Beanie per family” rule that accompanied a high-stakes release, and secure the latest addition to his collection.

Weekends and afterschool hours were spent “doing inventory:” Listing Beanie names and prices, placing a protective cover on each Beanie’s tag, and organizing the animals by species and color. Robinson had to make sure his investment was secure—the stuffed animals weren’t for playing, they were a prized investment. To Chris, a father of five, the collection of toys represented a college fund for his family, and a bright future for his sons.

He was wrong.

Beanie Babies began as creator Ty Warner’s solution to traditional stiff stuffed animals that were not very cuddly or easy to pose. Although former co-workers have dubbed Warner a “smart-assed shithead,” the toys were successful from the start, and topped $6 million in revenue by 1992, thanks in large part to partnering with exclusive mom and pop shop merchants who were more likely than larger stores to highlight the toys. Beanie Baby sales doubled annually in the early 1990s, but the mania around them had only just begun.

After a disruption in manufacturing, Warner was forced to discontinue “Lovie” the lamb, one of the original Beanie Babies. Rather than admit a snag in his supply chain, Warner told stores Lovie had been “retired.” Consumers were instantly converted into collectors, relishing the idea that their “Lovie” might be worth more than what they had originally paid. Suddenly, Beanie Babies became something much more than children’s toys… and much less tangible.

Ty Warner immediately capitalized on this sudden spike in value, concentrated among a new demographic: adult collectors. After re-branding the products as collectibles and manufacturing an impression of scarcity through Beanie “retirement,” sales continued to rise at unimaginable rates; characters such as Patti the Platypus were being sold on eBay for upwards of $5,000. Chris Robinson, and his fellow collectors, kept buying, hoping that their investments would continue to multiply.

This inflation of value was not sustainable. Beneath speculation, the value of Beanie Babies was most significant to its intended audience: children. Speculation perverted the brand’s narrative from its original purpose—in fact, the real value of Beanie Babies has been replaced by an optimistic hypothesis about the future: a bubble of delusion.

That bubble didn’t take long to burst. One 1997 price guide predicted the Beanies would appreciate 8,000 percent within the following decade, but not even a year later, that prediction appeared impossible—even prices of the most valuable pieces dropped from $1,299 to $899 over just a few months. What were once “collectibles” were now among over 30,000 simultaneous listings in eBay’s “Beanie Baby” category, to catastrophic effect on families like the Robinsons.

A brands most sustainable value is how it is treasured by its audience. Speculators may cause momentary inflations, a temporary fad, or even a popular trend—but ultimately, the strategic narrative will revert back to those for whom it was crafted in the first place. Because collectors such as the Robinsons never treasured the Beanie Babies for their intended purpose, they were blind to what their investment was really worth.

Beanie Babies, now gathering dust on closet shelves and sitting lifeless on childhood beds, didn’t have to succumb to this fate. Ty Inc.—the company Warner founded to produce the toys—had the potential to construct a profitable Beanie Baby empire that persisted through generations. It was intoxicated in the same way collectors were—the initial promotional campaign for “Lovie” made it impossible to resist the urge to cash in on hysteria, and the responsible decision to hew more closely to their own narrative. Instead of embracing the brand’s purpose to create and nurture the emotional value of each piece in the present, and creating a community around that value, they embraced the Beanie Baby bubble—fleeting success in exchange for irrelevance in perpetuity.

One of Beanie Baby’s toy-shelf peers, however, avoided this dust-covered destiny. 1990s card game Magic: The Gathering remains both culturally and financially valuable.

The game has elements to satisfy any role player’s desire: wizards, sorcerers, enchantments, and creatures with names like Brushwagg, Hippogriff, Ooze, and Vedalken. The game was sold in packs of randomized cards; occasionally, an exceptional, powerful card would be tucked away in a pack. Like Beanie Babies, fans flocked to compile the perfect assortment of Magic: The Gathering cards, hunting down elusive cards that would fulfill their fantasies.

The game’s 1993 release was popular among a diverse audience that went well beyond the expected Dungeons and Dragons demographic, and generated so much consumer demand that parent company Wizards of the Coast was hesitant to advertise the decks in fear that production wouldn’t be able to keep up. By the end of that same year, the Seattle Times reported 10 million cards had been sold. By 1997, Newsweek reported two billion. With increasing sales, and the rarest of cards still elusive, Magic: The Gathering was primed for the same speculative behavior as Beanie Babies. A secondary market for the cards had developed, and cards were being sold for much more than their intrinsic value.

The price of the cards continued to rise. Rare cards were sought after not by committed players seeking a powerful aide in their games, but instead by collectors willing to pay thousands of dollars for a single card. George Elias, a game designer at the Wizards of the Coast, was uneasy with the bubble: “if you had enough money, you could effectively buy all the aces.”

While this appreciation was good for Wizards of the Coast—it drove sales—it was incongruent with the organization’s strategic narrative. It had to find a way to deflate the bubble without popping it, and return the game to its rightful place: “a cheap, fun game that you play with your friends.” After assessing the lifecycle of previous collectible bubbles such as comic books and baseball cards, Wizards of the Coast saw two options: make as much money as possible in the two years before the market collapsed, or sacrifice short-term profit to create a more sustainable product. They chose the latter.

Wizards of the Coast printed a slew of new card sets, pushing the price of each pack back down to the original price: $3. Collectors weren’t happy, but collectors aren’t the hero of Magic: The Gathering’s story. Players are. Magic: The Gathering cards were never meant to sit in plastic containers destined for attics and garages, like so many Beanie Babies continue to do.

Since Wizards of the Coast deflated this bubble and embraced its authentic self, Magic: The Gathering has continued to put a spell on players. The company was acquired by Hasbro in 1999 for $325 million, introduced the Pro Tour Hall of Fame in 2005, hosted its two-millionth DCI (Duelists’ Convocation International) sanctioned tournament in 2009, and is credited for driving Hasbro’s Q2 2019 growth by 14 percent. Today, an estimated 50 million people play Magic: The Gathering across the world. Its momentum is unrelenting.

If 2024 is a good year to be a Magic: The Gathering player, it’s a sad year to be a Beanie Baby. The owner of Las Vegas collector’s store cements their undesirability: “If you bring Beanies to me and try to sell them to me in bulk, I’ll give you about 20 cents. That’s me telling you I don’t want them. Give them away.” Had Ty Warner stayed focused on Ty Inc.’s true champion—children who craved a more loveable stuffed animal—and committed to the story he was telling them, perhaps the Beanie Baby bubble wouldn’t have collapsed. Instead, Warner was blinded by profit—not purpose.

Gary Larson, a worn-down ex-Beanie collector, reflects with sadness: “sometimes, things that sound like a great idea just don’t pan out.”

Kenly Craighill was an associate at Woden. Read our extensive guide on how to craft your organization’s narrative, or send us an email at connect@wodenworks.com to uncover what makes you essential.